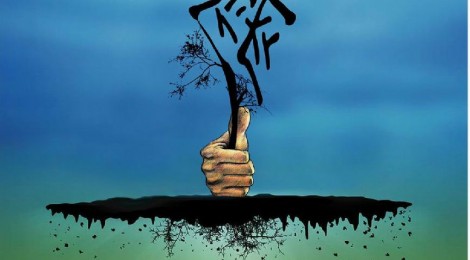

CCP cadres are trembling: China’s anti-corruption campaign

Since the beginning of 2016, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been putting a strong stress on enforcing moral standards and discipline in the selection of competent Party officials.

Liu Yunshan, a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CCP Central Committee, made his remarks during a meeting attended by the Party’s organization department chiefs from across the country, urging the CCP organizations to take responsibility in ensuring that official selection is properly conducted without unfair and corrupt practices. Official selection should emphasise candidates’ “ideological integrity, loyalty to the Party, diligent attitude, and sense of responsibility,” he said.

Although the CCP has made great progress in fighting corruption, there is still widespread concern about bribery in elections, buying and selling official positions, and illegal intervention in selection. In a speech at the Sixth Plenary Session of the CCP Central Commission for Discipline Inspection in January, Xi Jinping stated that a priority for the Party is a strictly implementation of CPP rules, including a tough fight against corruption, and the extension of anti-graft campaign to the lowest rank officials.

The CCP journal Qiushi underlined that the CPC leadership has shown determination to fight corruption since taking office in late 2012, and has improved officials’ sense of integrity. Former senior officials including Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai and Ling Jihua have been investigated and punished for graft in the past few years, as all officials have been under closer scrutiny for even minor violations of frugality and other Party rules.

Furthermore, the new year had brought the harshest disciplinary code since the time of Mao. For CCP members, regardless of rank, the Disciplinary Code of the Chinese Communist Party 中国共产党纪律处分条例 has come into effect since January 1 with dreadful punishments. These may occur because of an affair or for extensive overseas visits, according to the judgment of the Internal Supervision Regulation Committee (ISRC). The disciplinary codes have been labelled by some as “unbearable and inhumane”, reminding the darkest years of the Maoist era.

Furthermore, the new year had brought the harshest disciplinary code since the time of Mao. For CCP members, regardless of rank, the Disciplinary Code of the Chinese Communist Party 中国共产党纪律处分条例 has come into effect since January 1 with dreadful punishments. These may occur because of an affair or for extensive overseas visits, according to the judgment of the Internal Supervision Regulation Committee (ISRC). The disciplinary codes have been labelled by some as “unbearable and inhumane”, reminding the darkest years of the Maoist era.

The Code has greatly expanded the ISRC’s powers, which was previously a relatively marginal institution, and it is said to be far more potent than the law of the state. Besides establishing a disciplinary committee in every state organization, the ISRC can now remove the official under question on the spot and have him sent to law-enforcement agencies before the workday is over. Several Party members suggested that the “arrest first, question later” tactic is striking terror in the hearts of the Party’s ranks.

The code can be applied retroactively to cases that date from decades ago, as “no official, retired or not, can escape inspection.” As some of the acts now banned by the Code were grey areas in the old days, this post factum approach sounds very scary. Moreover, the current anti-corruption campaign is a hunt which often focuses on the past, drifting course from combating corruption to persecution.

The code might be interpreted as a phase in Xi’s revolutionary process, which breaks with the approach introduced with Deng and followed by all his successors, creating a new political order. According to some critics, the Code is not aimed at increasing government’s transparency and efficiency, as its anti-corruption campaign merely resulted in diffuse fear amongst bureaucratic elites, and might be used as a means to purge political opponents.