China in the Arctic. The Polar Silk Road

On January 26, China for the first time issued a whiter paper on its Arctic Policy, declaring that it will actively participate in Arctic affairs as a “Near-Arctic State” by seeking cooperation with Arctic states and other international as well as local entities to shape policies and outcomes (find the English full text here). The White Paper released by the State Council Information Office describes China as “an important stakeholder in Arctic affairs” and as a “Near-Arctic State, one of the continental States that are closest to the Arctic Circle.” The Paper goes on by saying that “the natural conditions of the Arctic and their changes have a direct impact on China’s climate system and ecological environment, and, in turn, on its economic interests in agriculture, forestry, fishery, marine industry and other sectors.” Sharing “interests with Arctic States,” China hopes to work with all parties to “jointly build a ‘Polar Silk Road,’ and facilitate connectivity and sustainable economic and social development of the Arctic.”

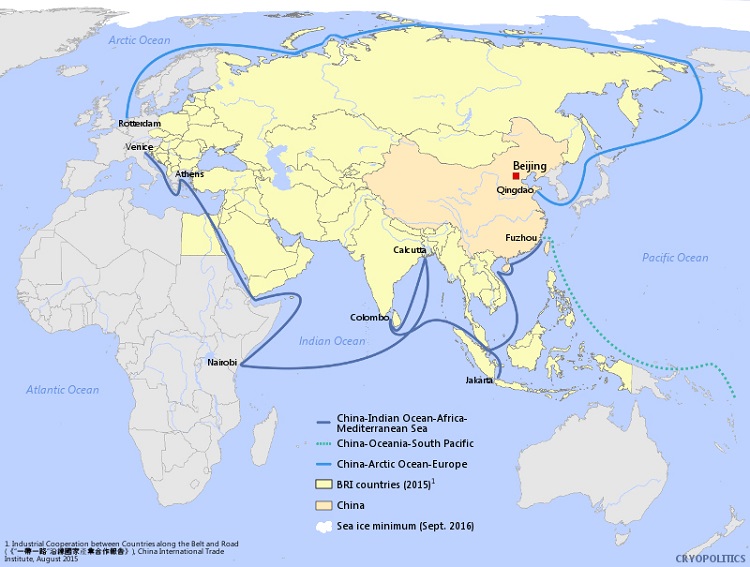

China’s perception of the Arctic has been increasingly strategic in the past decade. Initiative such as the Polar Silk Road could indicate a coming surge in Beijing’s economic and political endeavours in the region. The reaction to China’s declaration on the Arctic has been mixed. While many countries are secretly anxious about Beijing’s intentions, the support from some Arctic countries, especially Russia, on the Polar Silk Road greatly boosts China’s confidence and opportunity of progress. Of course, China cannot avoid working with Russia, which borders much of Arctic. In 2016, China’s state-owned Silk Road Fund (part of the Belt and Road Initiative) completed a deal to buy a 9.9% stake in liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant in the Russian Arctic for $1.2 billion. The plant is majority-owned by Russia’s LNG producer Novatek and China will be the main customer for the gas produced. Russia has been a key factor in China’s proposal to build the Polar Silk Road. Chinese President Xi Jinping first raised the project with Russian Prime Minister Medvedev in July 2017. In the broader context of warm ties between Beijing and Moscow under Presidents Xi and Putin, Russia has its eyes on Chinese investment in energy stakes in its Far North as well as the northeast shipping route, which presumably is the shortest sea lane of communications between Northeast Asia and Western Europe.

China’s strategy in the Arctic region will be mostly based on four aspects:

- China will participate in the development of Arctic shipping routes which are composed of Northeast Passage, Northwest Passage, and the Central Passage. Given that the Arctic shipping routes are likely to become important transport routes for international trade, China will encourage “its enterprises to participate in the infrastructure construction for these routes and conduct commercial trial voyages;”

- China aims to participate “in the exploration and exploitation of oil, gas, mineral and other non-living resources” in the Arctic. However, the White Paper also places particular emphasis on non-traditional energy resources;

- China will start to utilize fisheries and other living resources and participate in conservation;

- China will develop Arctic tourism, which the paper describes as “an emerging industry.” For instance, Finland’s Lapland region saw the number of Chinese tourists jump over 90% in 2016.

China’s current priorities in the Arctic seem to be focusing on three areas. In terms of commercial interests, the White Paper emphasizes the exploration of natural resources and the development of the Arctic shipping lane. In terms of global challenges, China is focused on climate change, environmental degradation and sustainable development in relation to the Arctic. Beijing identifies the Arctic as a platform to experiment with its role in global governance: China has adopted a series of policy initiatives, including enhancing scientific research, promoting the role of multilateral fora on Arctic affairs, enhancing political and economic bilateral coordination and cooperation with willing Arctic states, pursuing commercial cooperation with local indigenous peoples, and improving policy studies related to the Arctic.

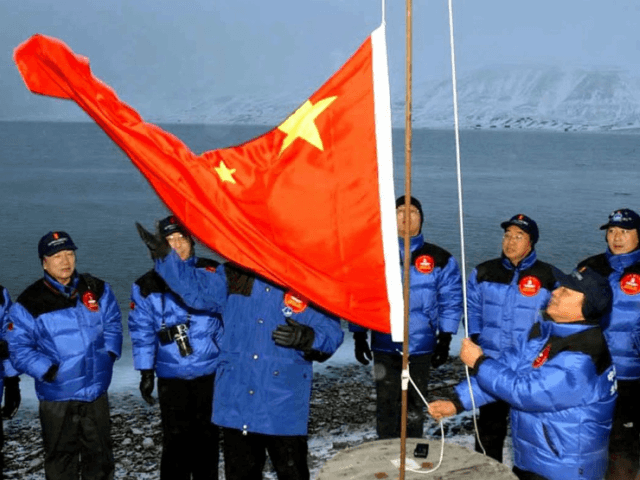

Although the issue of military security is completely left out the White Paper, in the past five years, the Naval Command College and Naval Research Institute of China have conducted three Arctic research projects under the National Science Research Fund. One of them is on the establishment of a supply base in the Arctic and the other two are about the Arctic shipping lane. Keeping the military issue out of the paper suggests China’s unwillingness to raise too much attention to its nascent strategy in the Arctic, and indicates that soft approaches through investment and cooperation are high on Beijing’s agenda to open the door to the polar region.

The logic of the Polar Silk Road follows China’s overall rationale on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). There is a lack of infrastructure and a need for financing and technologies to increase the economic connectivity and potential of the Arctic region. To use infrastructure as a way of pushing into an unfamiliar or unfriendly domain has become a pattern for China. The focus on the Arctic shipping lane falls under the mandate of building connectivity projects, the key feature of the BRI.