Chinese women are trying to reach their half of the sky

On Tuesday this week, all around the globe Women’s Day has been celebrated in many different ways. Multinational companies have embraces the holiday, turning it into another opportunity for consumerism. Yet, the roots of the celebration lie in grassroots demonstrations in Russia on 8 March 1917, where feminists were fighting for higher salary and better working conditions. After Vladimir Lenin declared 8 March an official festivity in 1922, Women’s Day was adopted by Communist China in 1949 and celebrated mainly by socialist countries till the mid-1970s.

In 2016, the celebrations come just a few months after the adoption of the first law on domestic violence in China. This represents a huge progress for a country where domestic violence has been considered a family matter, and therefore to be handled privately up until the end of 2015, when the law was introduced. Before China’s legislature passed the law, Chinese women who went to the police to denounce physical violence, were receiving the following response: that’s a private matter, go home. After years of feminist organising and advocacy, this is considered a hard-earned victory. However, advocates also say the law is deeply flawed, as it fails to account for sexual violence, and it is silent on the matter of same-sex couples. Also, some noted the biggest challenge will be the law’s implementation.

As for women’s standards of living in general, though China’s government is right to note improvements in welfare and health, the full picture is more complex. Chinese women are, on average, wealthier, more educated and healthier than they were before, but experts say they are losing ground, relative to men.

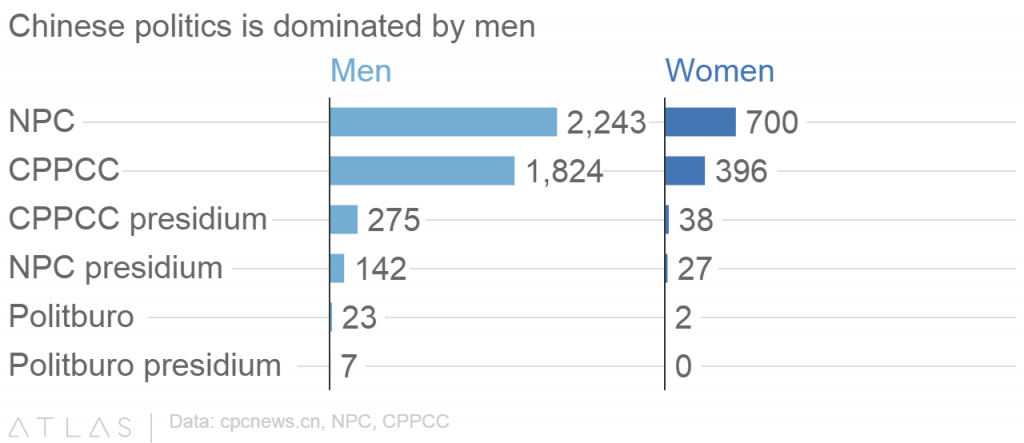

Women’s Day occurs just as China’s “Two Sessions” meetings gather some 5000 Chinese Communist Party members and advisers in Beijing to plan the political and economic year ahead. Even if China’s media insists female deputies’ voice are being heard in the two sessions meetings, China’s government, and particularly the top levels of government, is still overwhelmingly dominated by men.

In fact, there seems to be some evidence that things are going backwards for women in China. Earlier this year, the government shut down a renowned women’s centre – Beijing Zhongze Women’s Legal Counselling and Service Centre – that has been providing legal advice on sexual harassment in the workplace, domestic violence, and divorce proceeding, among other issues, for 20 years. In November, a Beijing art exhibit about feminism and domestic violence was shut down before it opened.

Regarding the job market in China, there is still a lot of discrimination. For instance, employer can decide to advertise jobs solely for men. Also, the change to the one-child policy – which has yet to be put into effect – has consequences for women. While it should hopefully end the worst practices – such as forced sterilisation and abortion – there are women lamenting: “now we have to sacrifice for the nation by having two children”.

On top of this, protesting to demand equal rights seems to become increasingly dangerous. Last year, five feminists were arrested on Women’s Day for planning a protest against sexual harassment by handling out stickers on public transport, and have been imprisoned for 37 days. On this year’s anniversary, one of them, Li Tingting, spoke out in a YouTube video thanking Beijing for “pushing the feminist movement to another peak” by detaining them. Li said that was “the first time that the international community knew that there are real feminists in China.”

Campaigning for women’s right since 1949, the All China Women’s Federation does so on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party, and it is criticised for promoting a vision of womanhood that puts marriage and children above all else, while refraining them from pursuing higher education. In the video, Li says she’s now campaigning against forced marriage, because she wants women to know that marrying a man is not necessarily the key to a “happy life.”