Circle of Friends – Interview with Professor Silvia Pozzi about her new translation of “Ghost Town”

Silvia Pozzi is full professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Milano-Bicocca and scientific director of the “Officina Permanent Translation Lab“, a research and training laboratory in the field of literary translation. She is also editor-in-chief of the Italian edition of the magazine “Chinese Characters” of “People’s Literature”.

Focusing on contemporary literature and its translation, she has a wide range of interests, and her translated works have been recognized by many international literary award selection committees. She started to work in literary translation in 1999. During this period, she has translated works by writers such as Tie Ning, Yu Hua, Alai, Can Xue, A Yi, Lu Min, Lu Nei, Lin Bai, and Liu Cixin. Her main works include Yu Hua’s “Brothers”, “The Seventh Day”, and “Wencheng”.

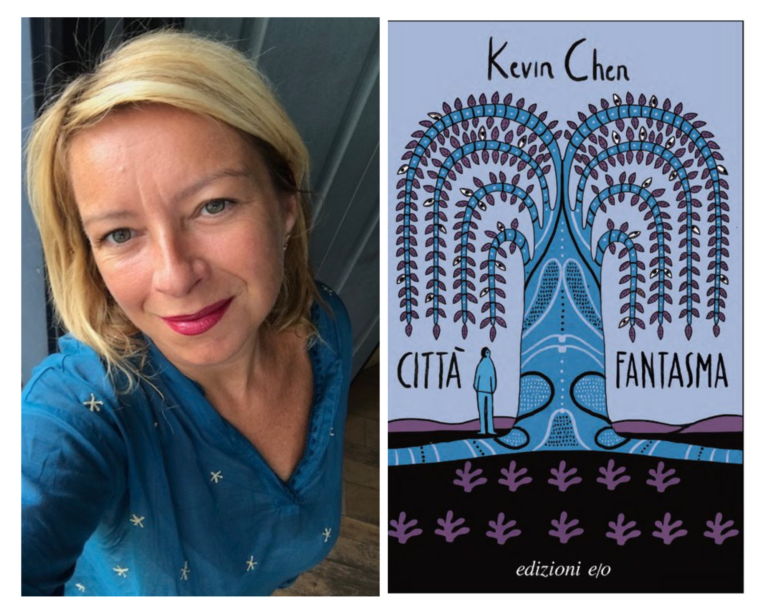

Her latest traslation is “Città Fantasma” by author Kevin Chen published by Edizioni E/O. We had the opportunity to discuss with her the contents of this new book and her job as a translator.

Enjoy this interview both in Italian and English!

Nel lavoro di traduzione di questo libro, quali sono state le maggiori sfide ma anche le maggiori sorprese che ha incontrato? In translating this book, what were the biggest challenges but also the biggest surprises you encountered?

La storia di Città fantasma si svolge in un giorno solo, nel pieno della canicola estiva, il quindicesimo giorno del settimo mese del calendario lunare, che coincide con la Festa degli Spiriti quando, secondo la tradizione, le porte dell’inferno sono aperte. In ognuno dei 45 capitoli la narrazione avviene tra continui flashback dal punto di vista o del protagonista o di uno dei membri della sua famiglia, chi morto, chi vivo: cinque sorelle maggiori, un fratello maggiore, il padre e la madre. Quindi una prima grande difficoltà che ho dovuto affrontare è stata quella della resa dei piani temporali. La lingua cinese consente una maggiore mobilità nello spazio-tempo, l’italiano con la sua rigorosa consecutio temporum talvolta evidenzia una minore duttilità nei salti temporali. Ho riscritto il testo varie volte, cambiando ogni volta il tempo della narrazione principale per approdare infine al presente indicativo. Sia la versione francese che quella inglese fanno invece ricorso al passato. In definitiva sono soddisfatta di avere fatto questa scelta, che mi sembra restituisca al meglio i molteplici monologhi interiori dei personaggi. L’altra grande sfida di questo testo è la sua lingua “lussureggiante”, che ho dovuto cercare di “domare”, come ha detto il giornalista del Corriere della Sera Marco Del Corona in un’intervista a Kevin Chen comparsa su La Lettura. Sono pagine gonfie di pensieri, immagini, ricordi, in un’interpretazione superba della tecnica del flusso di coscienza: scelte lessicali improvvide da parte del traduttore rischiano di minare la comprensibilità del testo, che deve scorrere come un fiume in piena. A questa sfera appartengono anche vari nodi che ho tentato di sciogliere relativi a termini culturalmente collocati, i cosiddetti realia, che da sempre costituiscono un grattacapo per i traduttori dal cinese. Ad esempio, il romanzo è costellato di termini che contengono il carattere gui (fantasma, spirito), a cominciare dal titolo che letteralmente è “Posto di fantasmi”, ma è anche un modo per dire “posto sperduto”. Oppure il titolo di uno dei capitoli è “Parole di fantasmi”, a intendere che si tratta di parole non affidabili, assurde e che nella mia resa è divenuto “Cose dell’altro mondo”.

La sorpresa (e il sollievo) più grande di questo lavoro è stato accorgersi solo all’ultima ed ennesima revisione di piccoli particolari che riecheggiavano tra loro a distanza di centinaia di pagine nel testo, consentendomi di ripensare alcune soluzioni di resa. Ogni opera è un mondo a sé, ricco di richiami intratestuali ed extratestuali.

The story of Ghost Town takes place in a single day, in the middle of the summer heat, the fifteenth day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, which coincides with the Festival of the Spirits when, according to tradition, the gates of hell are open. In each of the 45 chapters, the narration takes place through continuous flashbacks from the point of view of either the protagonist or one of the members of his family, some dead, some alive: five older sisters, an older brother, the father and the mother. So the first big difficulty I had to face was the rendering of the temporal planes. The Chinese language allows for greater mobility in space-time, while Italian with its rigorous consecutio temporum sometimes highlights less flexibility in temporal jumps. I rewrote the text several times, each time changing the tense of the main narration to finally arrive at the present indicative. Both the French and the English versions instead use the past. Ultimately, I am satisfied with having made this choice, which seems to me to best convey the multiple interior monologues of the characters. The other great challenge of this text is its “luxuriant” language, which I had to try to “tame”, as Corriere della Sera journalist Marco Del Corona said in an interview with Kevin Chen that appeared in La Lettura. These are pages full of thoughts, images, memories, in a superb interpretation of the stream of consciousness technique: imprudent lexical choices by the translator risk undermining the comprehensibility of the text, which must flow like a river in flood. This sphere also includes various knots that I have tried to untie relating to culturally situated terms, the so-called realia, which have always been a headache for translators from Chinese. For example, the novel is dotted with terms that contain the character gui (ghost, spirit), starting with the title which literally means “Place of Ghosts”, but is also a way of saying “lost place”. Or the title of one of the chapters is “Words of ghosts”, meaning that these are unreliable, absurd words and that in my translation it became “Things from the other world”.

The greatest surprise (and relief) of this work was to notice only at the last and umpteenth revision of small details that echoed each other hundreds of pages apart in the text, allowing me to rethink some rendering solutions. Each work is a world in itself, full of intratextual and extratextual references.

Professor Pozzi with Chinese author Yu Hua

Perché leggere questo libro? Che cosa aggiunge all’ampia offerta di titoli asiatici presenti nel nostro paese? Why read this book? What does it add to the wide range of Asian titles available in our country?

Innanzitutto vorrei precisare che l’offerta di titoli cinesi e in particolare taiwanesi non è propriamente ricca. Certo negli ultimi anni si traducono più titoli, ma tuttora manca una traduzione in italiano direttamente dal cinese dei grandi romanzi di epoca Ming e Qing ad esempio (l’unica eccezione è Il sogno della camera rossa nella bella traduzione di Edoarda Masi). Da Taiwan abbiamo qualcosa di Bai Xianyong, Chi Ta-wei, Qiu Miaojin, Wang Zhenhe, Wu Ming-yi e poco altro. La varietà di sguardi, di racconti, è sempre sinonimo di ricchezza. In particolare, questo romanzo di Kevin Chen ci porta una ventata di aria fresca. Spesso abbiamo un’idea preconfezionata delle letterature della sinosfera, la verità è che non ne sappiamo nulla, così come nulla sappiamo di quei mondi e delle genti che li abitano, delle loro tradizioni locali e della loro quotidianità.

First of all, I would like to point out that the range of Chinese and especially Taiwanese titles is not exactly rich. Of course, in recent years more titles have been translated, but there is still no translation into Italian directly from Chinese of the great novels of the Ming and Qing eras for example (the only exception is “The Dream of the Red Chamber” in the beautiful translation by Edoarda Masi). From Taiwan we have something by Bai Xianyong, Chi Ta-wei, Qiu Miaojin, Wang Zhenhe, Wu Ming-yi and little else. The variety of points of view, of stories, is always synonymous with richness. In particular, this novel by Kevin Chen brings us a breath of fresh air. We often have a prepackaged idea of the literatures of the Sinosphere, the truth is that we know nothing about them, just as we know nothing about those worlds and the people who inhabit them, their local traditions and their daily lives.

Questo libro è una finestra su Yongjing, un paesino sperduto in mezzo a una pianura piatta, a est in lontananza verdeggia la catena montuosa che è la spina dorsale dell’isola. Il posto è piccolo e retrogrado, la campagna con coltivazioni di crisantemi e foglie di betel a perdita d’occhio è popolata di serpenti e leggende, la modernità lì non è ancora arrivata, la gente chiacchiera e come in ogni altro luogo del mondo le malelingue possono ferire nel profondo. Il romanzo è anche uno specchio delle sofferenze dell’animo umano, dei traumi che si tramandano di madre in figlia e di padre in figlio, di tutto quello che ci fa abietti e della bellezza che ci rende immortali per un istante. La lettura è sostenuta dalla scoperta progressiva dei segreti dei personaggi. Il primo mistero del romanzo compare già nelle prime pagine: perché il protagonista (alter ego dell’autore) Chen Tien-hung ha ucciso T, il giovane tedesco che aveva preso come marito?

This book is a window on Yongjing, a small village lost in the middle of a flat plain, to the east in the distance the green mountain range that is the backbone of the island. The place is small and backward, the countryside with chrysanthemum and betel leaf crops as far as the eye can see is populated by snakes and legends, modernity has not yet arrived there, people gossip and like in any other place in the world gossip can hurt deeply. The novel is also a mirror of the suffering of the human soul, of the traumas that are passed down from mother to daughter and father to son, of everything that makes us abject and of the beauty that makes us immortal for an instant. The reading is supported by the progressive discovery of the characters’ secrets. The first mystery of the novel appears already in the first pages: why did the protagonist (the author’s alter ego) Chen Tien-hung kill T, the young German she had taken as a husband?

Professor Pozzi during the “China (Henan)-Italy Education Exchange Forum”

Dal punto di vista della scrittura, in che cosa eccelle l’autore Kevin Chen? Quali sono i temi principali delle sue opere? In quali aspetti pensa che sia un autore da leggere e valorizzare? From a writing perspective, what does author Kevin Chen excel at? What are the main themes of his works? In what aspects do you think he is an author to read and value?

Kevin Chen (classe 1976) ha iniziato la sua carriera artistica come attore cinematografico, recitando nei film taiwanesi e tedeschi Ghosted, Kung Bao Huhn e Global Player. Ha pubblicato diversi romanzi, saggi e raccolte di racconti, tra cui Attitude, Flowers from Fingernails, Three Ways to Get Rid of Allergies. L’autore attualmente vive a Berlino, tuttavia ambienta molta delle sue opere in un “posto da fantasmi” come Yongjing, che è la sua città d’origine così come la capitale del suo mondo creativo seguendo un topos ben documentato in letteratura. Le sue storie però sono tutt’altro che prevedibili. Grazie alla sua fantasia vulcanica e a una sensibilità molto raffinata, sa descrivere scene familiari, paesaggi della natura o i meandri della mente con immagini potenti, evocative e molto toccanti. Questo non gli preclude un ricorso sapiente all’ironia. Yongjing fa da contenitore all’universo uomo. Inevitabile quindi che leggendo le opere di questo autore oltre a un angolo remoto di Taiwan, con le sue usanze, le sue tradizioni, i suoi cortocircuiti, il lettore finisce anche per scoprire se stesso.

Kevin Chen (born in 1976) began his artistic career as a film actor, starring in the Taiwanese and German films Ghosted, Kung Bao Huhn and Global Player. He has published several novels, essays and collections of short stories, including Attitude, Flowers from Fingernails, Three Ways to Get Rid of Allergies. The author currently lives in Berlin, however he sets many of his works in a “ghost place” like Yongjing, which is his hometown as well as the capital of his creative world following a topos well documented in literature. His stories, however, are anything but predictable. Thanks to his volcanic imagination and a very refined sensitivity, he knows how to describe familiar scenes, natural landscapes or the meanders of the mind with powerful, evocative and very touching images. This does not preclude him from a wise use of irony. Yongjing acts as a container for the human universe. It is therefore inevitable that by reading the works of this author, in addition to a remote corner of Taiwan, with its customs, its traditions, its short circuits, the reader also ends up discovering himself.

Pozzi was awarded at the Ceremony of the 17th Special Book Award of China in 2024

Come organizza il lavoro delle sue traduzioni, ha dei luoghi che preferisce o delle routine che segue a ogni libro? How do you organize your translation work? Do you have any favorite places or routines that you follow for each book?

Traduco in modo del tutto disorganizzato. In primis perché lavoro all’università e i miei impegni accademici mi consentono di dedicarmi alla traduzione principalmente di notte, nei fine settimana e durante le vacanze. Inoltre la mia creatività ha bisogno di concentrarsi per esprimersi: dopo avere letto il testo in cinese passo settimane a meditare sulle soluzioni, in qualche modo la traduzione comincia già a prendere forma nel mio cervello, quando poi è il momento giusto avviene come una sorta di detonazione interiore e allora mi dedico a un lavoro matto e disperato al computer in ogni momento libero. Ho bisogno di tuffarmi integralmente nella traduzione per rendere al meglio, nei periodi di pausa didattica ne approfitto per ritirarmi per alcune settimane in una residenza per traduttori all’estero (in Svizzera, Svezia o Germania) e per 14 ore al giorno non faccio altro. Vorrei comportarmi diversamente, soprattutto per la mia salute, ma non ne sono capace. In questi periodi faccio sonni brevi e popolati dai personaggi dei libri che sto traducendo, in un certo senso non esco dal lavoro di traduzione nemmeno nella vita onirica. Arrivo alla consegna della traduzione sfibrata, sempre dopo avere compiuto numerose revisioni, e il tempo che dedico alla rilettura delle pagine finali dell’ultima revisione si dilata ogni volta. È un po’ come se non volessi chiudere con quel lavoro, come se provassi una sorta di senso di abbandono. Quel libro per un periodo della mia vita è stato la mia vita.

I translate in a completely disorganized way. First of all because I work at university and my academic commitments allow me to dedicate myself to translation mainly at night, on weekends and during holidays. Furthermore, my creativity needs to concentrate in order to express itself: after reading the text in Chinese I spend weeks meditating on the solutions, somehow the translation already begins to take shape in my brain, then when the right moment comes it happens as a sort of internal detonation and then I dedicate myself to crazy and desperate work on the computer in every free moment. I need to immerse myself completely in the translation to perform at my best, during periods of teaching break I take advantage of it to retreat for a few weeks to a residence for translators abroad (in Switzerland, Sweden or Germany) and for 14 hours a day I do nothing else. I would like to behave differently, especially for my health, but I am not capable of it. During these periods I have short sleeps populated by the characters of the books I am translating, in a certain sense I do not leave the work of translation even in my dream life. I arrive at the delivery of the translation exhausted, always after having completed numerous revisions, and the time I dedicate to rereading the final pages of the last revision expands each time. It is a bit as if I did not want to finish with that work, as if I felt a sort of sense of abandonment. That book for a period of my life was my life.

During an event about her translations

Traduce da tantissimi anni con grande successo – quali sono stati i risultati o riconoscimenti che più le hanno fatto piacere e resa orgogliosa? You have been translating for many years with great success – what results or awards have made you most happy and proud?

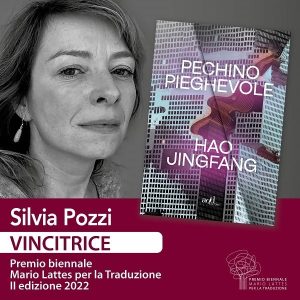

Ci sono i riconoscimenti ufficiali, che sono importanti, soprattutto per una traduttrice dal cinese: siamo ancora più invisibili dei traduttori letterari di lingue come l’inglese, lo spagnolo, il francese o il tedesco. In questo ambito ho avuto l’immenso onore di ricevere dei premi molto importanti, ho ricevuto il Premio Nazionale per la Traduzione del Ministero della Cultura nel 2021, il premio biennale Mario Lattes per la traduzione dal cinese nel 2022 e lo Special Book Award of China nel 2024. Ma ci sono anche altri riconoscimenti, meno vistosi, meno chiassosi, che pure ti riempiono di orgoglio e gioia perché sono un segno che la tua dedizione ha dato frutto. Succede quando un lettore o una lettrice ti abbracciano per ringraziarti perché leggendo Brothers o Il settimo giorno di Yu Hua o Montagne e nuvole negli occhi di Wu Ming-yi si sono commossi fino alle lacrime. Non succede spesso, ma succede, ed è un’esperienza indescrivibile.

There are official awards, which are important, especially for a translator from Chinese: we are even more invisible than literary translators of languages such as English, Spanish, French or German. In this field I have had the immense honor of receiving very important awards, I received the National Translation Award from the Ministry of Culture in 2021, the biennial Mario Lattes award for translation from Chinese in 2022 and the Special Book Award of China in 2024. But there are also other awards, less visible, less noisy, which also fill you with pride and joy because they are a sign that your dedication has borne fruit. It happens when a reader hugs you to thank you because reading Brothers or The Seventh Day by Yu Hua or Mountains and Clouds in the Eyes by Wu Ming-yi moved them to tears. It doesn’t happen often, but it happens, and it’s an indescribable experience.

Professor Pozzi recently won the “Biennial Prize Mario Lattes” for the translation of “Folding Beijing”, a masterpiece of Chinese literature

Perché secondo lei, è importante tradurre opere dal cinese all’italiano? Why do you think it is important to translate works from Chinese to Italian?

Perché ci sono opere meravigliose, intense, stupefacenti scritte in cinese e doversene privare rende tutti più poveri. Tanta bellezza non può e non deve essere appannaggio solo dei pochi italiani che conoscono il cinese. Lentamente e progressivamente la domanda del mercato letterario per titoli cinesi, taiwanesi, hongkonghesi ecc. sta crescendo. Anche il numero dei traduttori cresce ed è essenziale che la riflessione sul lavoro del traduttore e sulla qualità della resa dal cinese all’italiano sia tenuta in grande cura. A differenza di altre combinazioni linguistiche non esistono ancora in Italia consolidate opportunità di formazione ed è a questo scopo che insieme ad altre giovani colleghe ho istituito in seno al dipartimento di Scienze Umane per la Formazione dell’Università di Milano-Bicocca il laboratorio Officina di Traduzione Permanente [https://officina.formazione.unimib.it/en/homepage/]. Ci confrontiamo sulle nostre traduzioni, facciamo traduzioni e creiamo occasioni di formazione. Tradurre opere dal cinese all’italiano è importante per i lettori italiani, ma è ancora più importante farlo al meglio, non solo per i lettori italiani, ma anche per gli autori cinesi.

Because there are wonderful, intense, amazing works written in Chinese and having to deprive ourselves of them makes everyone poorer. Such beauty cannot and should not be the prerogative of only the few Italians who know Chinese. Slowly and progressively the demand of the literary market for Chinese, Taiwanese, Hong Kong etc. titles is growing. The number of translators is also growing and it is essential that the reflection on the work of the translator and on the quality of the translation from Chinese to Italian is kept in great care. Unlike other language combinations, there are still no consolidated training opportunities in Italy and it is for this purpose that together with other young colleagues I have established the Permanent Translation Workshop [https://officina.formazione.unimib.it/en/homepage/] within the Department of Human Sciences for Education of the University of Milan-Bicocca. We discuss our translations, we do translations and we create training opportunities. Translating works from Chinese to Italian is important for Italian readers, but it is even more important to do it well, not only for Italian readers, but also for Chinese authors.

Interview by Marco Bonaglia