Galilei Circle of Friends – Interview with Danilo Soscia

Danilo Soscia (1979) writes for newspapers, websites and literary magazines. His most recent publications are Atlas of Wonders (2018) and The Nocturnal Gods (2020) both for the publisher Minimum Fax.

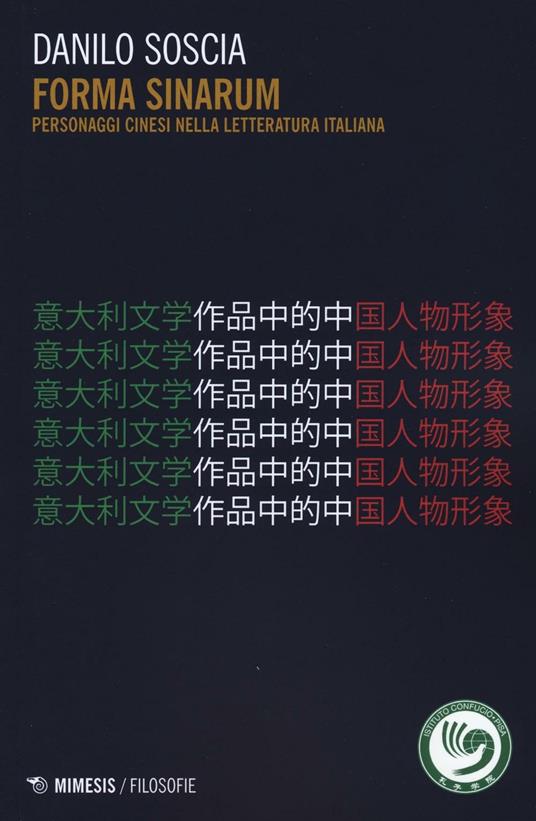

With regards to China research, he wrote two books, “In China” (2010) with ETS Edizioni, and “Forma Sinarum” with Mimesis (2016).

Today we bring you his analysis of Italian writers books on their China travels and experiences. Enjoy it!

How did you approach travel literature by Italian authors in China?

My passion for travel literature goes back a long way. It responded to a desire to get to know places far away physically, but through the experience of others. There was something about travel memoirs that triggered my imagination more than fiction. An almost magical combination of reality narrative and reality itself. In travel writing, the piece of the world that is described is, after all, the great absentee of the narrative. There, reality is often hidden behind the form of the text, the point of view, the prior knowledge. It is almost impossible to look it in the eye for what it is. What we see, instead, is the protagonist of the journey, the one who says <<Me>>, his world to which he belongs, his dreams, his fears. Every journey, then, and every travel narrative is the tale of a utopia, in the etymological sense of the term, that is, the tale of a place that is not there, except in the desires of those who describe it. China, from this point of view, for nearly two millennia has been for the West the utopian counterbalance par excellence, a backdrop against which to project the full spectrum of its own condition. With the advent of technology, the reduction of distances, the intervening facilitations in the practice of travel, its presence has become more tangible. I was interested in accounting for this proximity, in understanding whether our view of that world had changed, or whether the underlying paradigm had remained more or less intact. Who better than writers could answer my question?

What did your “journey” through the works leave you with? What did you learn?

I have had a close look at what, perhaps improperly, I call <<textual knowledge>>. In my youth I was very impressed by the vulgate – almost an iconographic description – that, while crossing the Ocean, Christopher Columbus never lifted his gaze from two books: the Bible and the Milione by Marco Polo and Rustichello da Pisa. The keel of his ships marked a course almost unknown in human history, yet Columbus pursued to sail on the lines of the pages. In this image, a de facto unprecedented experience was in any case reduced to something known, as if the voyage were the means by which to confirm his previous knowledge. Travel, in a word, as eternal return. This may sound like a stretch, but in my study experience devoted to Italian writers’ travels to China, I have detected more than one element of continuity between the “Columbus complex,” so to speak, and certain strains of contemporaries, who likewise have not renounced traversing Chinese reality primarily through books.

Tell us about your books on this topic – when were they published, by which publishing house, how were they received, what is their central theme and their literary mission?

My production has been all in all haphazard. As opposed to an anomalous publication such as ‘In Cina’ (Ets 2010), somewhere between anthology and critical essay, and ‘Forma Sinarum. Chinese Characters in Italian Literature’ (Mimesis 2016), with a marked academic vocation, I have long collaborated with newspapers and magazines where I have disseminated numerous articles dedicated to contemporary China, always through the filter of literature, but also of cinema, of society. Let’s say that, at a certain point in my journey, I felt the need to take leave of the ‘written China’ and focus on themes more rooted in contemporary reality.

What do you think are the key themes explored by Italian writers/intellectuals traveling to China?

Rather than themes, I would talk about cultural dynamics. The constant element that we can deduce from reading the corpus of Italians’ travels to China during the 20th century is the comparison, at times obsessive, between the reality experienced and the narrative of that reality. Sergio Solmi was right when he said that Marco Polo’s Il Milione represented an inescapable scenario for contemporaries as well, but not so much for what was narrated in it, but for its form. The traveler is by definition a promoter of meaning-and in particular the traveler who elaborates a written memory of his journey-but such an ontology also premises the absoluteness of his own role, which very often prescinds from reality, distorts it, or simply reduces it to a meaning whose outline he has begun to elaborate long before departure. That is why, from the pages of Luigi Barzini in the early twentieth century to the ‘posthumous’ diaries of Renata Pisu in the 1990s, passing through dozens of names belonging to the twentieth-century canon, China coincides with its wonder, even when Mao Zedong finally brings down the curtain on one of the longest-lived empires in human history and inaugurates the current time. The one we have also come to know.

Why is it still useful for you to read their works?

Because they represent a document of exceptional utility for understanding a way of translating the other, cultural diversity, that still in the globalized world dictates its age-old rules. Each of us, before tackling one of the many travelogues to China made by an Italian author, should ask ourselves: what is my idea of China today? And then trace his or her answer back to the pages he or she gets to read. He will notice how there is not a great distance between his own idea and the one of many travelers of the last century. Why? Perhaps China is no longer the reservoir of utopias that it has been for centuries on this side of the world; perhaps China today materializes for us an uneasy, elusive scenario, even an antagonist in some ways, or on the opposite side an opportunity, a land of promise, an indispensable interlocutor in the global strategic landscape. In a formula: in our imagination, China is still a complement, a reality that exists by virtue of one function: to embody our counterbalance. But is this truly the case?

Almost certainly not, but it is a very complex legacy to deconstruct.

What could be the differences between their works and the more recent ones by Italians in China?

Certainly in recent years more attention has been paid to the epiphenomena of Chinese reality. This has always seemed to me to be an attitude in line with certain demands of our contemporary times, but also a way of breaking down the problem from the more external aspects that, with patient observation, can reveal a link to the substance, to the hidden core. Odeporics in a classical sense has lost its exploratory vocation for now, perhaps because a trip to China is no longer a voyage of discovery. It is a debate that has already become ‘classical’. I am referring to the so-called ‘end of travel,’ that is, the inability of contemporary individuals to travel to discover, precisely, but only to certify. In a brutal summary, this is a formula that tries to summarize the metamorphosis of the traveler into a tourist. Yet I have always believed that this perception is strictly a product of our times, and also of our need — I mean ‘we’ as a civilization — to come to terms with our colonizing heritage.

The discovery now nestles in the small, even in microscopic things. One would say in the grain of rice, just to stay true to a particular imagery about East Asia. The travelers and writers of our time come to terms with a reality that is certainly no longer remote either spatially or culturally. But are we really sure that China, our ancient counterpart, has fully unveiled its heart to our eyes? The challenge lies in going in search of those ganglions where the unknown still lurks, and trying to describe it, this time attempting not to interpose any lens between us and another us, and giving up the logic of centrality from which to observe the rest of the world. China is China: a tautological statement but as close to the truth as ever. It is up to the new pioneers to make this claim their own.

Interview by Marco Bonaglia