Gaokao and inequality in education: how to fix it?

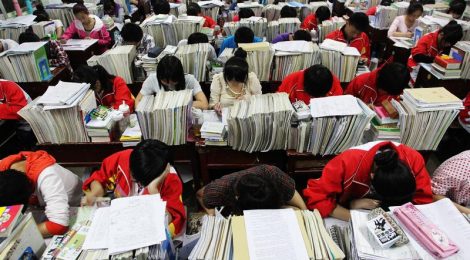

Last week, on June 7 and 8, more than nine million Chinese high-school graduates attended the gaokao 高考, the national exam that corresponds to the Italian maturità, but also represents the watershed that bring students to college, or not. The performance during the exam will determine which university the students will access, therefore having a unmeasurable impact on their future.

The gaokao tests the competencies in Chinese, Mathematics, English and another science or humanities subject of personal choice. Apart from a break during the period of Cultural Revolution, the national test has been run all across the country since 1950, but its origins are much older, dating back to ancient times. In fact, the gaokao is shaped on the nation-wide examinations that were used by the Chinese emperor to select state bureaucrats; after been introduced in its first version during Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), every civil servant working for the empire has been selected trough imperial examinations up until the abolishment in 1905.

Nowadays, China’s top schools are concentrated in the big prosperous cities, mainly lying along the coast, while weaker and underfunded schools are mostly located in inland regions. Over the last two decades new schools and institutions for higher education have been opened, with university enrolment reaching 26.2 million in 2015, from 3.4 million in 1998. However, the coincidence of economic slowdown and the drop of job prospects for college graduates in recent years have prompt widespread concern about the opportunities to access top-quality higher education.

Until very recently, the children of migrant workers had no right to sit the gaokao in the cities, even if it is where they have resided and studied for the majority of their academic life, but had to go back to their place of origins to take the test. Even if intended to enhance social mobility and open up the universities to anyone who scored high enough, the gaokao has been criticised for having the opposite effect. The rural residents, who already receive a far lower quality education in comparison with their urban counterparts, have been largely excluded from the access to the country’s top school because of their rural hukou.

In the effort of alleviating the social divide between urban and rural residents, the government has introduced new measures to expand access to university for students from underrepresented regions. Also, some provinces awarded extra points to students belonging to ethnic minorities. China’s President Xi Jinping himself argued that high levels of inequality could shake the party’s hold on power, and the government has been trying to take action by investing in education in poorer areas.

Effective or not, the new measures have triggered various protests in major cities from parents claiming for “fairness in education.” This happened especially after the announcement of the Minister that, to make room for students coming from less developed regions, it would have forced schools to admit fewer local students. In Wuhan, parents surrounded government offices to demand more spots for local students. In Harbin they marched calling the new admissions mandate unjust.

Sida Liu, a sociologist at the University of Toronto, wrote to the New York Times that without the improvement of schools in the less developed regions we should not expect any major change in educational inequality in the country. If he is right, much of the work is still to be done by the central government.