Paris Climate Change Deal: Good for the Planet, Good for China

From November 30 to December 12, Paris hosted the 21st annual session of the Conference of Parties (COP 21) to the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. As it happened during the past edition in Lima, in December last year, the final hours of the COP 21 have been fundamental to seal the final deal. On Saturday, with a one day extension, the parties in Paris reached what was called an historic agreement: 186 countries committed to take steps to limit global warming below 2° Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels, with the more ambitious target of 1.5°.

Following the disappointing conclusion of the 2009 conference in Copenhagen, this week’s deal was welcomed with enthusiasm by the most, as it led to a legally binding agreement which requires both, developing and developed nations, to take some form of action to fight global warming. It also contains provisions to hold countries accountable to their commitments and to assist developing nations in building low-carbon economies.

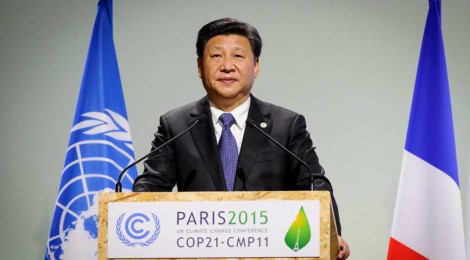

During the two weeks of consultations, China had been fending off accusations of stonewalling the talks, yet the situation reversed as the deal was unveiled on Saturday. As highlighted by US Secretary of State John F. Kerry, China’s constructive engagement helped pave the way to the new climate commitments. The working partnership between US and China, the world’s largest greenhouse gas polluters, represented a very important step along the way that enabled the deal. The first sign of this new cooperation was the bilateral meeting held in November 2014, when China agreed to cap emissions for the first time and the US committed to deep reductions by 2025.

Specifically, what China has committed to is peaking its CO2 emissions by 2030, and making best efforts to peak earlier. This means an increase of non-fossil energy up to 20 percent of its total consumption by 2030. Also, China pledged €2.8 billion to the South-South Cooperation Fund to aid developing countries to implement the post-2015 Development Agenda and address climate change. Other China climate commitments relate to carbon intensity, adaptation and forestry. In tandem with its international commitments, China has taken on massive energy programmes at home, making it the world’s biggest investor in renewable energy and plans to launch a nationwide carbon emissions trading market in 2017.

As reported by Xinhua, while making national pledges to secure global climate, “China has also taken an active part in international cooperation in climate change and provided assistance within its capability to other developing countries.” In so doing, China took the opportunity to showcase itself as a progressive superpower and responsible international stakeholder.

The outcomes of the Paris talks definitely represent a major achievement in the fight against global warming, meanwhile being in line with China’s domestic interests. During the second week of the talks, air pollution levels were skyrocketing in Beijing and the city’s authorities issued the first ever red alert: schools were closed, construction sites shut down and millions of cars ordered off the capital’s roads. On this background, Chinese leaders acknowledge a solution to China’s environmental crisis as national priority, also in reaction to an increasing public discontent and therefore as key to the Communist Party grip on power.

Pushing the country toward renewable energies represents for China an alternative to the traditional economic model, no longer feasible given the negative consequences of growth. Indeed, according to a joint study conducted by the World Bank and the Chinese government, air pollution alone may cost to the country up to $300 billion (€276 billion) a year. At the end of the day, China has a number of different reasons to make a strong shift to a more sustainable economy.